I only expect those with a keen interest in Book of Mormon trivia would catch this reference. More people are familiar with the Two Thousand Stripling Warriors

. The Sixty Warriors may very well be much more interesting than the Two Thousand. And that's saying something, because the Two Thousand are a pretty interesting case of manipulative teenage behavior gone right.

Yeah, you want me to explain that one. Well, keep reading.

The whole things starts with the People of Ammon (or the people ruled by King Lamoni, or the Anti-Nephi-Lehis, or the....I don't think anyone ever really decided what they should be called). The short story is that there was a group of people who were affiliated with the antagonists in the Book of Mormon that, through a series of events, converted to Christianity. Their fellow antagonsists didn't like this very much, so they declared war on the People of Ammon. The People of Ammon, having discovered an unprecedented level of shame and guilt over their war campaigns against the Book of Mormon's protagonists, declared themselves pacifists. They made a covenant never to go to war again, going so far as to bury their weapons and prostrate themselves before their attackers with hope of receiving mercy.

A grotesque slaughter ensued. The antagonists went so far as killing 1,005 of the People of Ammon before they got bored (Alma 24: 22). Apparently there's no sport in killing pacifists. In fact, many of the aggressors were so overcome with guilt from the slaughter that they joined the People of Ammon and took up the vow of pacifism (Alma 24:24-25). Soon after, the People of Ammon concluded they were not safe living near the antagonists and procured an invitation to join the protagonists. They were accepted as refugees, given land, and offered protection (Alma 27:22-24).

If you think that sounds like a happy ending, you'd be wrong. It would get worse for the People of Ammon. They took up their residence, and built a happy existence for themselves for about 13 years. About 8 years into that period, war broke out again, and the People of Ammon busied themselves in growing food and making supplies for their allies who were fighting on their behalf. But they were good hearted people, and to hear of the massive numbers of men being killed in war--men who would not go home to their families again, and whose children would be raised fatherless--it was burdensome. The cold irony of being someone who abhors killing others is that it is equally abhorrent to know that others are dying to protect you from doing that which you abhor. Add to that the fact that they seemed to be losing the war, and the People of Ammon were on the verge of making a choice to break their vow of pacifism.

The leader of the Christian church, Helaman, got wind of the rumors, and he rushed out to meet the People of Ammon (Alma 56:7-8). The Book of Mormon is pretty vague on the details of how this came about, but I have an idea of what took place.

While Helaman was busying himself to convince the People of Ammon not to break their oath, their sons developed a plan to save them.

"Mom, Dad, let us go to war.

We didn't make that oath.

We didn't promise God that we wouldn't fight. Let us go fight the war, and you stay home and keep your vows."

These young men could have ranged from 13 to 28. I would wager there were more of them close to the age of 20 than anything else. And I doubt that their plan was well received. "It's too dangerous. It's too horrific." The older generation had sworn off war because of the guilt they felt over killing other humans. I'm sure they weren't fond of the idea of exposing their children to that same horror. And I'm certain that they told their sons "No."

Unfortunately for them, they had raised faithful, god-fearing sons that also knew which buttons to push to convince their parents. "It'll be okay, mom and dad. We're going to ask Helaman to be our leader."

And their parents said, "Oh, well in that case, go ahead. Why didn't you lead with that?"

Okay, maybe it took a little more persuading, but in the end, the sons prevailed. They appealed to their parents' conviction that the prophets of God hadn't led them astray thus far, and so they felt they could put their faith in Helaman now. And I doubt there was anyone else in the world to whom they would trust their children.

Together, the parents and the sons would have had to convince Helaman. I'm sure he was terrified of leading these boys into battle. Afterall, he had no military experience to speak of. Taking this assignment was probably a bigger leap of faith for him than it was for the People of Ammon. And so Helaman gathered his Two Thousand warriors, and took them off to war.

Where do the other Sixty come into this, you ask? They came later (Alma 57:6). Some of these would have been boys that had come of age, but I'm convinced there were some whose parents forbade them go at first. And I don't blame them.

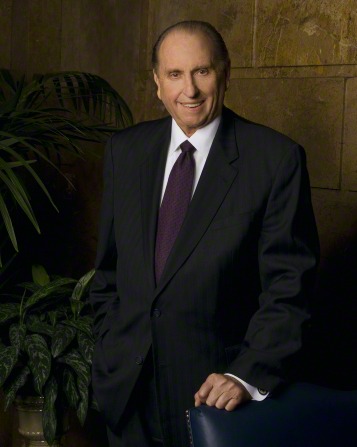

To put this in more modern terms, how would you respond if your kids came to you and said, "Mom, dad, I'm going to follow Thomas S. Monson into war." I even asked my Sunday School class yesterday if they'd follow President Monson into war. They unanimously said "no." In the words of one young man, "I'm not going to war with him. He's

old!" I wouldn't let my kids go either. And Monson even has military experience.

The parents of the Sixty, for whatever reason, doubted that sending their sons to war with a prophet was going to ensure their safety. They had to be persuaded first. Getting the reports back from the other Two Thousand--and seeing that not one of them was killed--probably helped build the case for sending the Sixty. With time, they developed the faith that was necessary to trust their sons to Helaman and to God.

What makes the parents of these Sixty so interesting is that they

had doubts. And they

still had firm convictions. These were parents who, although they doubted that doubling a prophet as a general would protect their sons, still chose not to break their vow of pacifism. You can't convince me their faith in Christ was any less than was those who sent their sons the first time. But with more evidence--and more importantly--more time for the Spirit of God to persuade them on their own terms, they did reach that point in their faith.

And their faith was rewarded. It's not like they sent their sons late in the game, and then their sons happened to get killed as a consequence of their initial doubt. All of their sons survived the war.

As with all things in the scriptures, they can be interpreted many ways. I imagine the more orthodox mormons would take this story and spin to to say, "See, there was no need for them to doubt. They should have just sent their sons to begin with. Their doubt was in vain."

But such an interpretation, I think, doesn't follow in the spirit of the scriptures. Those Sixty young men were received with joy. There was celebration that day. Celebration of the faith that parents exhibited, not criticism of the faith they didn't have earlier. Let us not forget that every parent of those initial Two Thousand had to come to terms with the possibility that their sons would not return. It seems cruel to criticize another parent for not yet being able to live with that possibility.

The story of the Sixty struck me profoundly this time around. I keep reading about words from General Conference. "

Doubt your doubts before you doubt your faith." And I keep hearing them used to argue that we should put our doubts aside because they challenge our faith. I hear this quote in that context and it infuriates me, because it completely ignores the paragraph that preceded the quote.

It’s natural to have questions—the acorn of honest inquiry has often sprouted and matured into a great oak of understanding...even in the sometimes sandy soil of doubt and uncertainty.

The parents of the Sixty cultivated their acorns into great oaks. They did so in sandy soil. They didn't do it alone. They did it with the love and support of friends and neighbors. They did it with fellow church members who gradually helped nurse that acorn by replacing the sand with rich soil. One shovel at a time.

Instead, I feel like we tell a lot of acorns to get out of the sand.

You can't pressure an oak tree to grow. You can't force it to grow over night. Growth requires time, patience, and nurturing. It requires friendship without boundaries, without judgment, and sometimes without completely understanding someone's doubts.

The parents of the Sixty live among us. Let's grow the forest with them.